I’ll never forget the day when my dad called and said, “Your mom had a stroke.“ I envisioned the scene where Forrest Gump jumped from his boat into the ocean as soon as he heard, “Your mama’s sick.” I wanted to jump into that non-existent ocean from Utah to Arizona. Having to wait for my brother to arrive from Salt Lake was terrible; having to wait until the next day to leave was torture. Our travel from St. George to Phoenix was a blur. When we arrived at the hospital, my mom was in ICU. Every time she asked why “they” were hurting her head, we tried to explain what happened, but she would just look at us as if we were speaking gibberish. We didn’t know, yet, that she couldn’t understand us. When my mom finally showed signs of improvement, she was moved out of the ICU to a private room on a regular floor.

During the week that she was in the hospital, she had a difficult time verbally communicating with us. About 90% of the time, she couldn’t understand us and would say that she couldn’t “hear” us. Additionally, her words were incorrect when she spoke. When she said the word food, she meant money; and, when she said the word money, she meant food. She would constantly use “much,“ “much much,” and “how much,“ in place of other words. At one point, my mom was able to communicate to my brother that she felt like she was put into a cage where she was told that she was no longer allowed to speak English, and people would only speak Finnish to her. When he realized that she was finger-spelling in the air to help communicate with us, my brother grabbed a pen and notepad and had her write down those words. It was then that we figured out that writing and reading would be the bridge of our communication.

During her hospital stay, writing on paper made it easier for her to converse with us; but, we had to remember to keep our side of the written interaction brief. She could write as many words as needed for her to form her sentences, but we could only write about three words at a time. We had to figure out how to shorten our points to no more than three words, or she would get confused.

One week after her stroke, she was moved to a rehabilitation center. This was where she began doing “homework” that consisted of worksheets where she had to identify simple pictures. She could write the name of the object, but she got frustrated when she couldn’t say the word correctly. It was difficult for her, because, her intelligence was still intact, but the ability to express her words wasn’t.

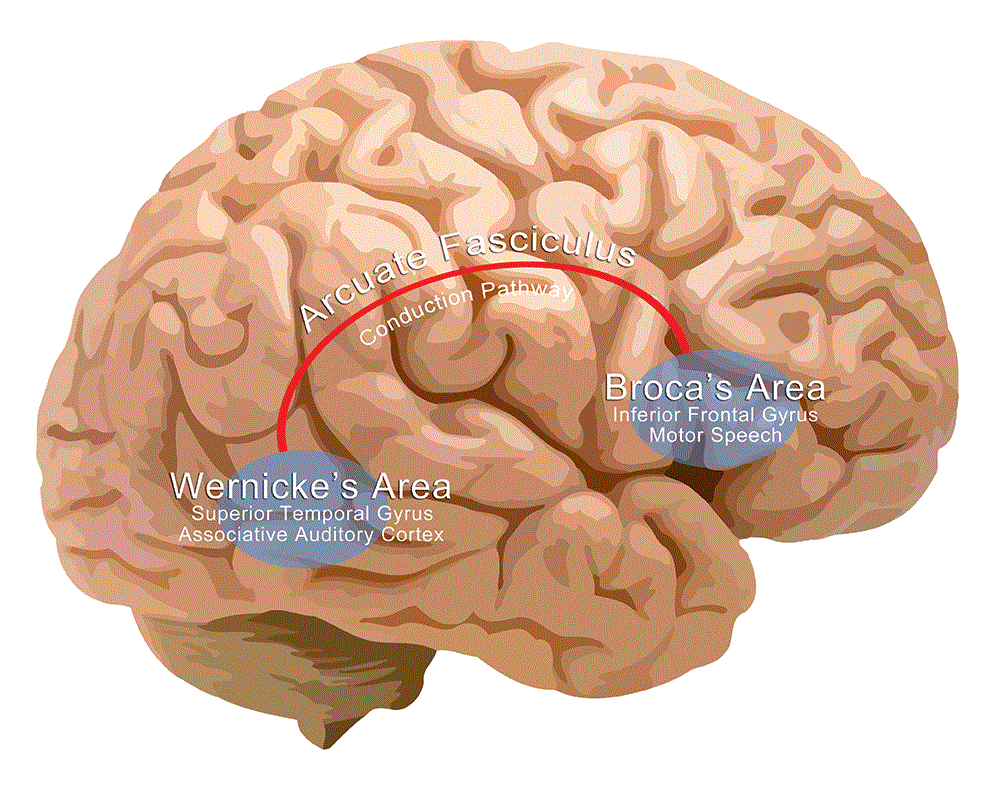

As soon as she got home, she went to speech therapy once a week. It was there that we learned what her diagnoses was: Wernicke’s aphasia. This meant that the area of her brain that helps make the connection of understanding and expressing speech was damaged. We were informed that the goal was to create a new pathway for communication within the Wernicke’s area. To create this pathway, a substantial amount of homework was required. My mom’s speech therapist assigned worksheets that consisted of paragraphs to read out loud and questions about those paragraphs. Basically, we were exercising Mom’s brain; however, for her, it was in an extreme fashion—what would have felt like a three-pound weight to us, felt like a 300-pound weight to her. The kicker was that we had only six months to do this with the speech therapist’s help. Her insurance company decided that any progress that was to be made would only be in the first six months after her stroke; therefore, they refused to cover speech therapy after the six month mark.

I stayed in Phoenix to help my parents during the first three months of my mom’s recovery. Three weeks after her stroke, and many tears of frustration on both of our parts, my aunt brought us some books that her third-grade students used for classroom reading. Of course my mom enjoyed these books more than her worksheets. Each day, after completing at least one worksheet, we would read from a couple of the young-reader books. She realized fairly quickly that she had an easier time understanding what she read because she knew the stories. This is when my mom decided to read her scriptures on her own. She knew them. She was relaxed when she read them. Their words gave her comfort. Even if she could only read a few words at a time, she knew that she would be able to understand them. The trick was to get her to be able to understand them when she read the words out loud. One night, I listened to my mom’s voice as it came from her room across the hall through the connecting vents, while she slowly read her scriptures out loud. She sounded out each word, trying to remember the meaning. This little task was a key component to rerouting the small path in her brain that had been damaged.

With each day, the process of creating sentences from the words she read aloud became easier. In addition, we recognized during the first few weeks of her therapy that if she was relaxed, she understood about 30% of what we said; if she wasn’t relaxed, she only understood about 5%. Over the months, her speech therapist was impressed with her progress; but, according to the insurance company, it wasn’t fast enough. My mom pressed forward, though. As she continued to read the simple books during the day and her scriptures at night, she gathered that it was the more difficult words from the scriptures that helped her progress the best. One day, while on our way out from one of her speech therapy appointments, we met a woman and her husband, who also had Wernicke’s aphasia. His wife told us that he wasn’t making much progression since his stroke and was worried about what she’d do after their insurance stopped covering his therapy. My mom asked his wife if he had ever read the bible. She said that they did before his stroke. Adamantly, my mom told her that they needed to start reading the bible again, since he knew it already. She declared that doing so would increase his progress immensely.

In time, Mom’s insurance ran out and her speech therapy stopped. Despite these set-backs, she pressed forward. For several years, her dear neighbor read books with her for at least one hour, three times a week. This not only gave my mom practice of understanding her own words, but she got to practice communicating with those outside of her family, as well.

It has been eight years since her stroke, and Mom has made tremendous progress because of the power of the written word. Now, when she is relaxed, she understands about 85% of what we say, and about 20% if she is stressed. In addition to reading her scriptures and other familiar books, my mom is reading and understanding novels, captions during television shows and movies, news articles, Facebook posts, letters and greeting cards, the captions on her Caption-Call telephone, and sentences that we write to help her better understand conversations. With all that we have learned and witnessed over the last eight years, we know that reading has played a major role in the healing of my mom’s brain. The new pathway is not complete; however, exercising her brain with the words of books, both old and new, will continue to create the necessary connection needed for her to regain her ability to understand and express speech. She may always have aphasia, but we know that as she continues to read, her brain will continue to heal. If you have a loved one going through the same experience, please don’t give up. Encourage them to continue to read!

Kim Kuhn

Kim Kuhn

Student Representative, Far Western Region, 2020-2021

Alpha Pi Epsilon Chapter, President

Dixie State University, St. George, UT

Sigma Tau Delta

Sigma Tau Delta, International English Honor Society, was founded in 1924 at Dakota Wesleyan University. The Society strives to

- Confer distinction for high achievement in English language and literature in undergraduate, graduate, and professional studies;

- Provide, through its local chapters, cultural stimulation on college campuses and promote interest in literature and the English language in surrounding communities;

- Foster all aspects of the discipline of English, including literature, language, and writing;

- Promote exemplary character and good fellowship among its members;

- Exhibit high standards of academic excellence; and

- Serve society by fostering literacy.

With over 900 active chapters located in the United States and abroad, there are more than 1,000 Faculty Advisors, and approximately 9,000 members inducted annually.

Sigma Tau Delta also recognizes the accomplishments of professional writers who have contributed to the fields of language and literature.

Add Comment